| Articles |

Material of the portal "The Guardian"Perhaps the real wonder – with low wages, strict new permits and openly racist apartment listings – is that any of the millions of Kyrgyz, Uzbeks and Tajiks who power Moscow’s huge economy are staying at all

A migrant worker watches a film on top of a shelter outside Moscow. Photograph: Denis Sinyakov/Reuters

For 12 years, Akbar has worked 12-hour shifts stocking shelves in a basement supermarket in central Moscow. Originally a chef from a small city in Uzbekistan, he would work most of the year in Moscow, then go home to visit his wife and five kids over New Year’s. But this year, the money’s got so bad that he plans to head back to Uzbekistan for good when his work permit runs out in August. “I’ll work until it expires, then go home. What is there to do here?” Akbar said as he stocked cartons of juice from a stepladder. “I’ll find work there. What else can I do?” His brother, who also works in Moscow, also plans to leave when his permit is up in December. Akbar, who declined to give his last name, is one of the many migrant workers who power Moscow’s huge economy. They man the construction sites, shovel snow and drive the hordes of “gypsy cabs” that take Muscovites home at night. More than a million of these workers are officially registered in the city, most from the former Soviet Union, and the actual number is likely much higher. In countries like Tajikistan, a major source of labour for Moscow, more than half the GDP is remittances sent home from Russia. Immigrant life is hard. Wages are low, and workers face discrimination and are poorly integrated into Russian society. Times have recently got more difficult than ever. The rouble has plummeted, and with falling oil prices and western sanctions, the World Bank is predicting that Russia will enter recession this year. Added to that are strict new regulations that cut further into migrant labourers’ earnings, leaving workers like Akbar rethinking their future. “Everyone’s leaving. Wages are small and many places are cutting salaries. Other workplaces are cutting jobs,” Akbar said. Last year saw a mass exodus of tens of thousands of German, American and British citizens. There were also large net decreases in the number of citizens from Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Azerbaijan, traditionally sources of cheap labour for Russia – although they were partly compensated for by an influx from Belarus, Armenia, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan (countries that have or are set to join the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union, established this year) and by a massive 858,000 Ukrainians fleeing conflict.

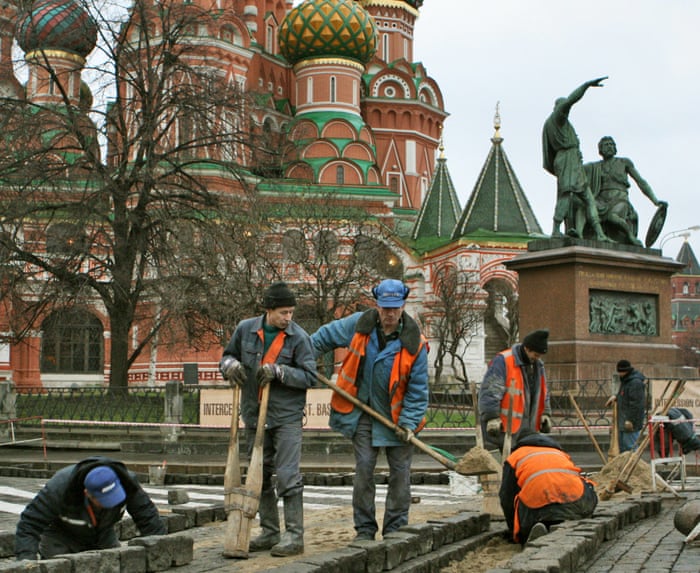

Workers pave Red Square outside St Basil’s Cathedral. Many are migrants. Photograph: Alamy Even so, reports suggest a downward trend in the number of labour migrants. The head of the Federal Migration Service said the number of immigrants entering Russia in the first half of January was 70% less than during the same period the year before. Yusuf Salimov of Tajik Railways said that during seasonal influxes in previous years, some trains carried up to 900 people from Dushanbe to Moscow. This year, he says, it’s been more like 100 to 150. Whether they’re playing to anti-migrant sentiments or just celebrating greater regulation, Moscow’s authorities have praised the change. “The latest data have shown migrants are leaving,” mayor Sergei Sobyanin said at the opening of a new unified migration centre in February. “This might stem from the economic situation but mostly from the financial regulations.” Sobyanin was referring to strict new rules on working in Russia. Citizens of former Soviet republics (besides the Baltics, Georgia and Turkmenistan) can enter Russia without a visa. But a new system that came into effect on 1 January requires migrant workers to get a “patent,” or work permit, for which they must take a medical exam against contagious diseases, get medical insurance and present Russian ID. They also must pass a test on Russian language, culture and history. Employers often employ migrant workers under the table, but the new system shifts the onus to pay tax largely on to the workers. A monthly fee – essentially an advance tax – must be paid to keep the permit open. In Moscow, it costs 4,000 roubles a month.

For a migrant worker making 20,000 to 25,000 roubles a month, that’s a lot. Akbar makes just 1,000 roubles a day. He pays 6,000 roubles a month to share a room in a communal apartment with two relatives and up to 10,000 roubles for food, transport and other needs. After the permit, he’s left with as little as 10,000 roubles (about $200) to send home to his family – a quarter of what he used to send. Others make even less. Olesya, a cleaning woman from Moldova, makes only 25,000 roubles a month and has been illicitly working without a permit. “How can I get a permit? My job doesn’t allow for it. I’d have to work a month for nothing,” she said, referring to the costs of the insurance, documents and fees. If caught, she could be barred from Russia for five years. The permit cost has worsened an already tough situation for migrant workers, who often face discrimination and persecution by crooked employers, officials and landlords. A quick search of rental announcements in Moscow will reveal that most listings are for Russian or “Slavic” people only. “It’s very hard to get a work permit. [Migrant workers] are deceived by officials and middlemen, and because of that they are constantly fined. They fear every meeting with a policeman, and employers are determined to pay them much less than a local – and often in the end don’t pay them [at all],” said Alexander Verkhovsky, director of the Sova Centre, which studies nationalism and xenophobia. Most apartment rental listings in Moscow ask for Russian or 'Slavic' people only Besides the discrimination they face, immigrants in Moscow are also poorly integrated into local society on the whole. Kyrgyz immigrants, in particular, live in a “parallel city” – relying almost entirely on their own countrymen for advice, information and basic services, said Yevgeny Varshaver, director of the Centre for the Study of Migration and Ethnicity. Although there is no “Kyrgyz Town” per se, Moscow has at least 80 restaurants whose clientele is mostly Kyrgyz, at least a dozen Kyrgyz hospitals and numerous Kyrgyz martial arts clubs, ticket-sellers, rental services and nightclubs. A key part of this infrastructure is the Mayak clinic, hidden away on the fourth floor of a weather-beaten brick building in northern Moscow. With doctors who speak central Asian languages and cheap prices for customers without insurance, Mayak’s main clientele is people from the former Soviet Union, especially Kyrgyz. According to deputy treatment director Salbek Abdygazeyev, who was born and completed his medical degree in Kyrgyzstan, about 50 to 60 patients come in every day. Half a dozen were waiting in the well-worn but clean corridor outside his office on a recent afternoon, where a television on the wall happened to be showing a debate on Channel One about immigration. “It’s harder at other hospitals. They speak Russian. Here they will explain everything in Kyrgyz,” said Eldar Abdrakhmanov, a chef. He said the out-of-pocket costs at Mayak were cheaper than at other clinics, since he doesn’t have health insurance.

Tajik migrant workers unload cabbages at a vegetable market in the Moscow suburbs. Photograph: Denis Sinyakov/Reuters “It’s our people here – Kyrgyz, Muslims,” said Kandzharbek Sartayev, accompanied by his son, daughter-in-law and two grandchildren. “They relate to us better here.” Abdygazeyev admitted “there are problems with integration”, but said he hoped the Russian language and history exams now required of migrants would help with this. It’s certainly a concern: about 70% of Kyrgyz people in Moscow said they associate mainly with other Kyrgyz, and half of these said they associate mainly with Kyrgyz they met in Moscow rather than acquaintances from home, according to Varshaver. This 35% is a vulnerable group that is marginalised and can “be turned toward bad or good,” he added. “It’s a problem of people not relating well to [immigrant] mothers at the playground, and of the large number of young village men who don’t feel the internal control that a person develops in a city, nor the external control like in the village,” he said. “People are sad and lonely, they live badly. But with integration practices, this group will come into their own.” Kyrgyz immigrants, in particular, live in a 'parallel city' – their own hospitals, ticket-sellers and nightclubs Varshaver and his fellow researchers have run programmes to help immigrants and Russians from the same neighbourhood get to know each other, including cooking classes and Q&As at local schools. They are planning a football league for Russian and immigrant men and are training 25 community organisers around Moscow to continue the integration process in their own neighbourhoods. The danger, however, is that the permits will be the final straw for many “sad and lonely” people. The downtick in workers has put pressure on Moscow’s economy. Industries involving cleaning, selling fast-moving consumer goods and construction are especially reliant on migrant labour in the capital, according to Nikita Mkrtchyan of the demographics institute at Moscow’s Higher School of Economics. As the population ages, there will be fewer people to work, and few Russians want the kinds of jobs migrants typically do, he said. “There’s a contraction of labour resources in general. If you look at immigrants who do construction, finding replacements quickly is hard,” Mkrtchyan said. “It’s not just in Moscow, but also in the regions. Russians don’t want to live in such hard conditions as migrants from the CIS.” Irina Rodionova, a manager at a cleaning business that has contracts with a number of shopping centres, said 30% to 40% of the company’s labour needs are unmet because lots of Kyrgyz and Uzbeks have left. In a bid to find more workers, it recently raised salaries from 15,000 to 20,000 roubles a month for men and from 12,500 to 17,500 roubles a month for women. “With the smaller salary, we couldn’t find anyone,” she said. “Every industry is in need of workers, except the restaurant industry because they offer free food,” said Anzhela Filipenko of the Migrant Workers Labour Union, who first arrived in Moscow as a migrant worker from Ukraine. Although she said employers will eventually be forced to offer higher pay or help with documents, that doesn’t mean workers’ lot will improve: many will simply try to squeeze more work out of fewer employees, she said. And yet as much as things have gotten harder for migrants in Moscow, many still have no choice but to stay. New job candidates arrive every day – many now from Ukraine, where the simmering separatist conflict, ongoing market reforms and huge foreign debt has led observers to predict a 5% to 10% contraction in GDP this year. “If America was next door, [migrants] would all leave,” Karimov said. “But what’s next door is Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, where the level of living is lower and there are no jobs. There’s nowhere to go.” Says Vladimir Anandiyev, 24, from Kirovohrad, Ukraine, who worked with his twin brother Vitaly at a construction materials store for four years until it cut wages and laid off staff this year: “[In Ukraine] you need to search for work, and even if you do find it, it will pay a low salary. Here, it’s bad. But there, it’s critical.” | |

| / |

Migrants workers from Tajikistan relax on the roof of their shelter after working at a local market outside Moscow. Photograph: Denis Sinyakov/Reuters

Migrants workers from Tajikistan relax on the roof of their shelter after working at a local market outside Moscow. Photograph: Denis Sinyakov/Reuters